"Here you can buy whale fillet in any supermarket, while radishes are exotic"

A Ukrainian family lived under occupation near Kyiv for a month. Now they are rebuilding their lives from scratch — in the Arctic.

Vardø Island. Northern Norway. The Arctic. A man and a woman stand at the entrance of a two-storey apartment building, smoking and huddling together. It's mid-May, and the wind is biting. Icy rain is drizzling. The man is in sportswear but without a jacket. The woman's dyed blonde hair is pinned up in a bun, and she's wearing a long black skirt, a t-shirt, and rubber flip-flops on bare feet. This is 47-year-old Elena and 49-year-old Sergei Boiko (surname changed at the request of the protagonists) from Ukraine. At the very start of the war, they spent 34 days under occupation in the village of Dymer near Kyiv, not far from Bucha. They escaped through a humanitarian corridor and have been trying to settle in the Arctic for the third year now, where they ended up, in essence, completely by chance.

Vardø is located on the coast of the Barents Sea and connected to mainland Norway by an underwater tunnel that runs 90 metres deep. It is one of the oldest towns in the Arctic. It used to be the capital of the so-called Pomor trade and Arctic discoveries, and in the 17th century, it was the centre of European witch hunts. It was on this island that trials took place, resulting in 91 people being convicted and burned at the stake. The Steilneset Memorial, dedicated to the victims of those terrible times, is a ten-minute walk from the house where the Boikos rent an apartment.

Currently, about two thousand people live on this island. Among them are our protagonists.

"Honeymoon"

I meet Elena and Sergei at the entrance as they light up another cigarette. It seems there's no one else on the street but us. Even the snow-white building of the Lutheran church, which is right next to their house, is closed. Every day, exactly at four, a church employee, a man about 35-years-old named Asgeir, arrives by bicycle. He opens it for tourists who arrive by ferry in Vardø at this time — for just an hour — and quickly explore this exotic island for them. Immediately after they leave, Asgeir closes the building. He is one of the few Norwegians the Boikos know; they even share baked goods with each other. The couple knows that every time after closing the church, Asgeir stops by a kiosk for ice cream and eats it right on his bicycle on the way home — "it's his tradition."

***

While living in Ukraine, Elena worked at a chemical plant in the Vyshgorod district near Kyiv, and her husband Sergei was an administrator in a grocery store. Their 27-year-old son, also named Sergei, lived with them; he graduated from college as a machinist-tractor driver and also worked in the store.

On the eve of the war, Sergei told his wife that for their 25th wedding anniversary, they should go on a trip to "some beautiful European country." They didn't have time to decide where exactly, but they started preparing their passports. Neither the husband nor the wife had ever been abroad before.

"Well, there you go, I jinxed it," Sergei now laughs sadly, sitting in the kitchen of a rented apartment in Norway.

Russian tanks entered the village of Dymer, where the Boikos lived, almost immediately after the war began — on February 25th.

"At four in the morning, we were woken up by the roar of tanks. For ten hours, the equipment was coming in. And it began," Sergei recalls.

The Russians came: searched, confiscated mobile phones. We also lost gas, electricity, and water in our homes. We wore white armbands and, together with our neighbours, went for food and medicine brought by the Russians. We thought this madness would last a couple of days.

But it didn't end and didn't end. Constant arrivals, explosions — we ran to the basement.

On the fifth day of the occupation, Sergei found an old radio and batteries for it in the attic of the house.

"It only picked up long waves. Sometimes there was something Russian — there was Solovyov, [with him] everything was clear, and sometimes the Ukrainian daily program "Television News Service" on channel 1+1 (then it was called "Marathon"). They said: "Everything is fine, everything is calm. Some hookah bar in Kyiv is opening, croissants." I stick my head out of the basement — and nothing is fine with us."

The Boikos' neighbour had half the roof blown off, windows shattered. They themselves had "arrivals" in their yard more than once.

"We quickly learned to determine by sound how long it would take to arrive. While it whistles, you must hide," says Elena. "Once I was standing in the yard — my husband shouted: "Lena, hide!" But where can you hide in a second? In front of me was a thin metal post, I hid behind it."

"Lenka once went to clean the raspberry bushes in the yard. At that moment, something boomed near her — and raspberries were no longer a priority," Sergei recounts with the same sad smile.

"Otherwise, you just go crazy," responds Elena. "As soon as there was a lull, we returned to normal life."

The Boikos say that they didn't want to leave their home until the last moment. But one day they had to sit in the basement for a whole day, and they felt that they were "really starting to lose it".

"And not just us," says Sergei. "A neighbour started walking down the street, singing songs. And once I was walking, and an elderly couple came towards me. The woman saw me and shouted to her husband: "Volodya is coming!" And she threw herself on my chest. Her husband led her away, saying: "It's not him, it's not our son, let's go".

"Ah, Ukrainian, scum"

At the end of March, the Boikos went to Red Cross volunteers for food distribution. They told the couple about the opportunity to leave for Belarus through a humanitarian corridor. And the Boikos decided they were ready — "for two or three weeks, until it all ends".

They packed one suitcase for the three of them: they put their Ukrainian passports in it (they didn't have time to get a foreign passport before the war started) and each had 'three pairs of trousers and three sweaters — just to have something to change into' during this short period. They put the rest of the documents and some things in two plastic barrels, wrapped them in film, and buried them deep in their yard. Among other things, they put photo albums, spices, kitchen gadgets, a will, and diplomas in these barrels.

"We were stressed. We wanted to save everything. And we couldn't choose what was more valuable because everything was valuable, everything was ours," explains Elena.

On March 30, the Boiko family left through Chernobyl to Belarus.

The corridor was brutal: mines, rockets, tanks, machine guns, — recalls Elena. — We were stripped 15 times, checked for swastikas or other tattoos.

Then they went through 'Belarusian filtration'.

"When returning the documents, the KGB officer asked me: 'Do you understand that you will never return home again?' I replied that yes, but in fact, I didn't realise it at the time," says Sergei.

The next six months, the Boiko family lived in the Belarusian city of Gomel, a hundred kilometres from their home. They deliberately didn't want to go far because they thought: 'It will all end soon.'

At first, they lived in the Mashynostroitel sanatorium, where they could stay for no more than a month. Then — at a volunteer's house. They were looking for work.

"But no one hired us Ukrainians for work — only as unskilled labourers 'off the books',"says Sergey.

As refugees, the Boiko family did not have official work permits in Belarus.

"To work as a janitor there, you need to study for three months and get a certificate that you are a janitor, and only then can you start working. Mowing grass, going into the forest as a woodcutter — the same thing," he adds.

But the main difficulty for the Boiko family was not even this.

"During the 2020 protests, Belarusians were divided into two camps: those who supported Lukashenko's policies and those who were against. After the war started, it was the same: one half for the Ukrainians, the other for Russia," Boiko shares his impression. "You go to apply for a job, some say: 'Dear ones, no problem. We'll arrange it now.' You go further in the direction, and there: 'Ah, a Ukrainian, you scum.' And they turn you away."

There were also difficulties in finding rental housing in Gomel.

"Most of the ads stated: 'We rent an apartment to everyone except people with animals and Ukrainians.' That is, we came after the animals," Sergei shrugs.

In the summer, the Boiko family went to the suburbs to pick strawberries to earn money for food. In five hours, according to Sergei, they picked 250 kilograms.

Then in June, the Boikos went to the market to look for an employer. They approached a woman and asked, "Do you need workers?"

"She looked at us and said, "No, we don't." We said, "We can do everything. We have nothing to live on. Nothing to eat." — In the end, they took pity on us and private individuals hired us, — says Sergei. "They had large greenhouses. The journey to work took three hours one way."

At the beginning of July, volunteers helped the Boikos to leave for Poland, where they were told it was easier to find work. By that time, all family members already understood that the war would definitely not end soon.

"We arrived in Poland at a distribution point. We ate, had coffee — they took us to the "Arena." It's a large sports complex with camp beds for a thousand people," says Sergei. "We ate again, drank coffee again."

"We approached and asked, "Where is Norway located?" A man replied, "Well, if you look at the map, it's there!" — pointing north. Lena asked, "Is it nice there?" He replied, "It's nice." We said, "We'll go." That's all we knew about Norway. After living in Poland for just two hours, we left."

"You see, when you're placed in a place with a lot of people, it's a shock," says Elena. "You want to leave there as soon as possible — anywhere."

"There will be no sun"

They travelled by bus to Oslo for almost two days and then took a ferry for another hour to the Rode municipality in southern Norway. There, their documents were checked and their application for temporary collective protection in Norway was registered. After that, the Boikos were sent to the Gålå area, where a ski resort is located. The family was accommodated in the Wadahl Høgfjellshotel at the very top of the mountain ridge. Other refugees from Ukraine also lived there. Many of them, especially those who wanted to be allocated to Oslo, waited there for five to six months.

"After a month and a half in this hotel, we were already going crazy," says Sergey. "The three of us lived in a room that was slightly larger than our tiny kitchen [where we are sitting now]. It was very picturesque there. We walked around. But the monotony was killing us. If the weather was good, we ran through the mountains, if not, we sat in the room on the internet."

Some people there just lost weight, dried up. The nervous system went crazy, especially for women. Because there was nothing to do. Plus, so many people in one place: arguments and intrigues began.

— says Elena.

There were no maids, everyone cleaned up after themselves, and they set up room duties: some did everything conscientiously, some did not. Plus, everyone was stressed...

After a month and a half, the person responsible for allocation approached the Boikos and asked, "Where do you want to go?" They replied that they "didn't care." "Will you go north?" The Boikos clarified, "Are there few people there?" "Few," the interlocutor replied. And they agreed: "Then fine, we'll go."

"We thought, since it's the north, at least there would be work there," says Sergei. "And few people — that's good, because it means it's peaceful there."

"And then we looked at the map to see where this Vardø is — we were horrified. Oh my goodness... It's in the Arctic," says Elena.

To get to Vardø, the Boikos first took a taxi, then a train, then a bus, and then flew by plane.

"Oh, how we flew!" Elena now recalls with a smile. "The plane landed, we stood up and were ready to get off, but they told us: "No, next". We didn't know that planes here land to pick up people and fly further, like buses. People boarded, and we flew further. — And we didn't believe the stewardess," says Elena.

"We were rushing to the exit," laughs Sergei.

The Boikos arrived in Vardø on the first of September 2022. It was raining, "the wind was such that you could touch it with your hands." The Boikos had never seen anything like it before.

"Everything here was incomprehensible to us!" says Elena, exhaling with the realisation that this period is behind them. "It's still unclear now, but we've gotten a bit used to it."

A few months after the Boikos moved to Vardø, the polar night began there — a time when the sun doesn't appear above the horizon at all, and the days consist only of twilight and darkness. This period starts at the end of November and lasts until mid-January.

"When I was told there would be no sun, I was shocked," recalls Elena. "I asked: How can there be none?" They replied: "There just won't be any."

The first year, the polar night was especially hard for us. There is no natural light at all, and artificial light starts to weigh on you, and you feel like you're going blind. You can't write or read. And we are of a certain age.

"And in May the polar day began," continues Sergei, Elena's husband. "We were told: "The sun won't set." We asked: "How can it not set?!" In the first year, during the polar day period, we didn't even have clouds. The sun just went around in circles. It was mind-boggling."

In winter in Vardø, the winds were so strong that Sergei even had to meet his wife from work and walk her home:

"The wind was stormy. People were blown off the streets. Once, even the two of us were carried by the wind, we barely held on.

No one in the Boiko family speaks English. When they arrived in Norway, they were enrolled in Norwegian language courses. A couple of times a week they studied it in a language school, and on other days they were sent to work at enterprises to practice the language there.

"Lena went to work at a school, and my son and I were builders-carpenters," says Sergei.

The Boiko father and son were sent to restore old buildings, replace windows and doors. Meanwhile, Elena worked in after-school care with primary school students. During this period, the Boikos received social benefits, but their work was not paid.

We communicated with colleagues using Google Translate. Although there are many dialects in Norway, the translator doesn't recognise them. So we resorted to gestures, bits of English we remembered here, and scraps of Norwegian.

There were comical situations. In turn, we taught the Norwegians our swearing, laughs Sergei. A colleague drops something on his foot, he looks at me: [Should I say] 'Blyad'? I reply: 'Yes. Blyad'.

'And I was asked if I wanted to run away from home to here?'

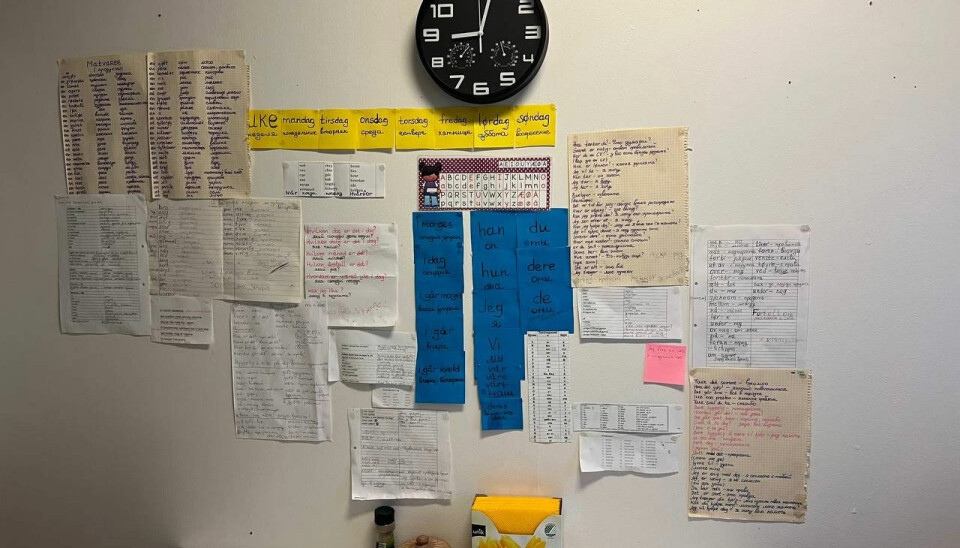

Stickers with words in Norwegian and their Russian translations are attached to the wall above the kitchen table in the Boiko's apartment. Months, days of the week, names of products. Above them hangs a clock. In addition to the time, it also shows the temperature and humidity level.

The top of the fridge is cluttered with jars of vitamins.

"To calm down, to sleep, to perk up, to compensate for the lack of sun, and Omega-3," comments Elena.

In the first year and a half of living in Vardø, the Boikos even gained weight.

"At first, we ate under stress and couldn't stop. We stocked up. We wanted everything. We ate a kilogram of oranges a day, ate a lot of sweets," says Elena. "We finally felt some ground under our feet."

After finishing language courses, Sergei tried to find work as a builder and in other companies in Vardø on his own.

"Remembering their names is a killer," he laughs again. "We had one at work named Steven, another was Kulga, and we, with our other Ukrainians, called him Colgate for simplicity, like the toothpaste. Norwegian itself is difficult. And then there are the dialects!" he adds.

"In the local language courses, we were taught bokmål (one of the two official written standards of the Norwegian language — Ed. note), but not everyone speaks it in Vardø."

I worked as a builder on the fishing pier. We sat with a group of fishermen, they talked among themselves, then a colleague came, also Norwegian, and said something. He left — they asked each other: "What did he say?"

During the six months that the Boikos attended language courses, they had six different teachers — "and each taught us different dialects, so every time it was like starting over."

Elena mostly silently observed the work of the Norwegian teachers at her job, only occasionally interacting with the children.

"I couldn't speak at all, and it was just very scary and awkward," she admits.

After completing the language courses, Elena temporarily got a job in the library archive. There she worked with Norwegian documents from the post-war years: sorting them by year and direction.

The local bosses are loyal, calm. No one shouts or swears. They ask ten times a day if you need help.

— says Elena.

Finding a permanent job in Vardø, according to the Boikos, is extremely difficult.

"There's a tricky scheme here," says Sergey. "To hire someone for a permanent job, they first train them for three months. During this period, they are paid a salary that is less than the social benefit. The benefit is 8,100 Norwegian kroner, and the salary during training is 6000 (and the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration provides these companies with subsidies to cover part of the wages for refugees during this period. — Ed. note). And after three months, the person is sent home and not hired. Instead, they take the next Ukrainian."

The Mayor of Vardø, Tor Erik Labahå, sees the situation differently. "I am not familiar with the Boiko family's case, but I know that many refugees from Ukraine have managed to find permanent jobs after the adaptation programme provided by Norway," he says.

"Vardø is a small town with not many businesses, but since the war in Ukraine began, we have taken in a lot of refugees, in proportion to the island's population," Labahå adds. "Our motivation was transparent: we wanted to lend a helping hand to people in need. We did this with caution and determination and continue to bear this responsibility. But at the same time, it is extremely important that the refugees themselves actively participate in the introductory programme we provide and genuinely want to learn Norwegian. Without knowledge of the language, it is impossible to find work."

Despite the belief that Norwegian employers cheat in employing Ukrainians, the Boikos themselves always consciously entered this three-month probation period, losing a quarter of their income. They hoped to eventually secure permanent jobs and earn more.

But now Elena and Sergei live on social benefits. Elena is looking for a job, Sergei is on sick leave due to back problems. Only their son works, as an administrator in a grocery store.

His job is also temporary.

Besides the Boikos, there are currently about 150 refugees from Ukraine living in Vardø.

"Some couldn't stand this nonsense and left for other countries," says Sergei. "Some returned to Ukraine, saying it's better under the bombs than all this. Some went to Russia. More precisely, through Russia — to Mariupol. They received Russian passports."

In Norway, as in other European countries, there is a system of temporary collective protection that allows Ukrainians to receive the necessary assistance. A residence permit is issued for a year, with the possibility of extension up to four years. But it is not a basis for obtaining a residence permit and subsequent legalisation in the country.

Norway has helped us a lot. We were well received, we were integrated. Everyone just thought the war would end quickly: in a year, two at most. But it keeps going. And Norwegians just don't know what to do with us next.

— says Elena.

The Boikos do not plan to leave yet, although they also have no clear idea of where and how to live next.

"Zero plans. We live for today. Tomorrow will be more interesting. We perceive it all as an adventure. It's easier for us that way. This is our honeymoon," says Sergei.

"Some of our people (Ukrainians. — Ed. note) gave birth after moving here, some managed to find permanent work, bought a house. Life goes on, the years pass, you can't rewind them back," Elena underlines. "You need to accept reality as it is. We, our family, are together — and that's a huge happiness."

"We have long since lost the illusion that everything will end quickly. Now we understand: the territory [of Ukraine] is sold, all these negotiations are a theatre. Politicians are simply resolving their financial issues. It will last until the last Ukrainian. If we had stayed at home, my son and I probably wouldn't be alive now," adds Sergei. "All our neighbours have been taken [to the front]. A classmate was recently returning home, and they grabbed him by the scruff — and into the car. He calls us, says: "I've been taken." Just like that.

While we are talking, Elena and Sergei suggest going downstairs, they need to smoke. By their entrance, despite the cold, right on schedule, just in time for summer, dandelions have sprouted. And they are tall and lush.

"Here flowers grow very quickly and become quite large, not like ours," explains Elena. "Because here the summer is very short. They need to live quickly. And the bumblebees here are small, like flies."

The Lithuanians, with whom Sergei worked here on construction, reproached him that Ukrainians quickly received some documents that they, the Lithuanians, had been waiting for for six months.

"I say: did anyone ask me if I wanted to flee from home to here? I was thrown onto a rocky island where there are no trees, nothing. In Ukraine, we lived in our own house, we had four seasons. I would gladly be there now," he laments.

In Vardø, according to Sergei, the only entertainment is fishing and the internet: 'We're going crazy.'

Throughout our conversation, Elena tries to shift her husband's mind, and her own attention, to positive moments.

She says that when she lived in Ukraine, she loved embroidering pictures with beads in her free time. In Norway, beads were impossible to find, but she found a solution: she orders kits from a marketplace where you stick diamonds by numbers to create pictures. Recently, she completed a set with lilies, and now she is about to start on daisies.

"There are a lot of birds here. Last year, many whales came. They were far away, but we could see their backs from the shore," Elena says. "We even bought binoculars to watch them."

What impressed both Boiko spouses the most in Norway was the low crime rate.

"You can leave a bicycle, and no one will steal it," says Sergei.

I was shocked that the teacher talked on the phone, put it on the table, and went to drink coffee. I thought the children would take it. But no. They are taught from childhood not to steal.

— Elena shares her husband's amazement.

Being in a completely new environment, the Boikos still try to live in it the old way, as they are used to. For example, this Easter, they took a table out into the courtyard of their house. They prepared salad olivier, stuffed cabbage rolls, salad shuba, and croutons. They invited friends. But there were snowdrifts around, and a strong wind was blowing.

"The box of tissues flew away. The tissues scattered so beautifully. Like fireworks," recalls Elena.

And they moved the table and the celebration to the basement.

Sometimes the couple goes mushroom picking.

"There are a lot of mushrooms here. Boletus, chanterelles. And the most interesting thing is that you can't get lost: there is no forest here — the mushrooms grow in the rocks," says Sergei.

When asked how they have changed in the new environment over the past few years, Sergei and Elena respond that they have become more closed off here.

"It's not like at home. Here everyone lives their own life," explains Elena. "After what we went through in Ukraine, I didn't want to communicate with anyone, see anyone. And people here didn't bother us. That's very good. They themselves live very privately, in families. They greet you and like it when you greet and smile back. But nothing more. Sometimes they come up to talk, ask something, but rarely."

Norwegians, as the Boikos found out, know little about life in Ukraine. Sometimes they asked Elena: 'Do you have potatoes? Tomatoes? Have you tried apples at home? Do you have any fruits there at all?' Such questions from Arctic residents amuse the couple.

The Boikos have occasionally encountered something familiar in the Arctic. Once, while walking near the sea, they noticed something growing near the rocks that looked like sorrel.

"We are from the countryside: we picked it and tasted it — yes, indeed, it was sorrel," Sergei rejoices. "Norwegians don't eat sorrel, but we gathered it and made green borscht at home!"

The range of grocery stores is still unusual for them:

"Here you can buy whale fillet and sausage made from it in any supermarket, while radishes are sold in packets of five, like an exotic item."

"And another time, two people knocked on our door: “Do you believe in God? We are Jehovah's Witnesses.” Lord, they used to bother us at home, and now here too. It doesn't seem right. The end of the world. In the neighbouring town, there's a sign saying “End of Europe,” and here they are," Sergei says with a surprised look. "I close the door behind them, thinking: oh, my dear ones!"

This article was originally published in Russian. Read the Russian version here.