Meteorologists: "AI can't replace us yet"

The Norwegian Meteorological Institute (MET) has been monitoring sea ice for decades. The maps it produces are one of the most reliable sources of data on climate change.

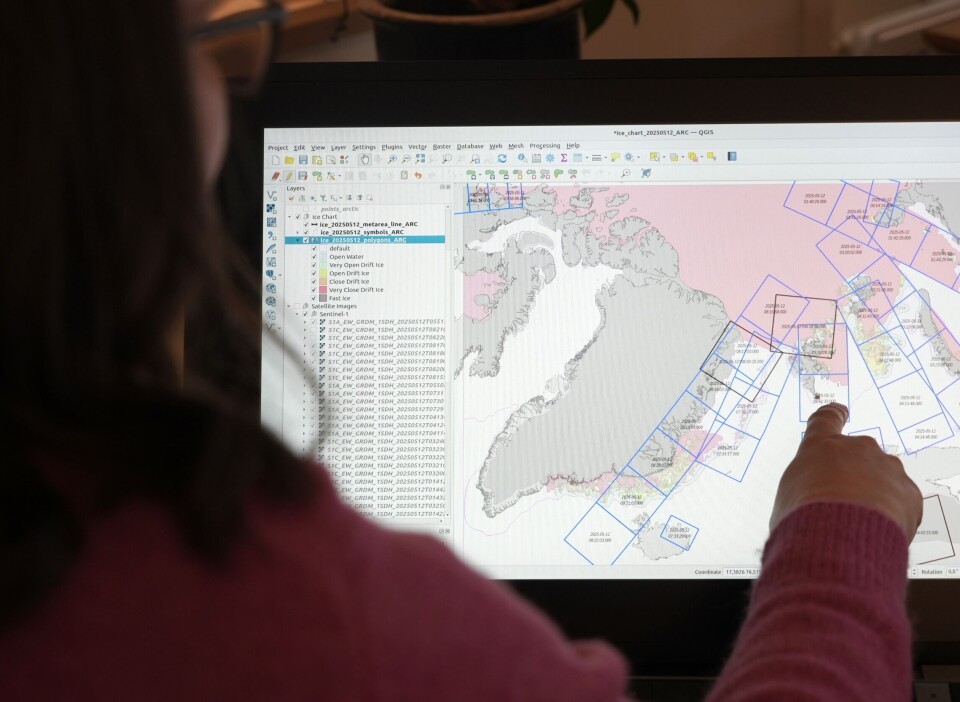

"You can see here - this year has had the lowest Arctic sea ice extent for January, February and March, since we started to use satellites for monitoring the sea ice in 1978", says Frode Dinessen, a researcher at the Meteorological Institute (MET), pointing to the sea-ice chart on his computer.

He and his colleagues produce such maps every day. Based in Tromsø, northern Norway, MET researchers not only monitor the weather, but also keep a close eye on the extent of polar sea ice throughout the year. The daily monitoring of Arctic waters is essential for science, but also for international shipping - many routes pass through the icy waters near Svalbard.

Even though the monitoring is now digitalised and satellites transmit the crucial data, the final maps are still made by hand:

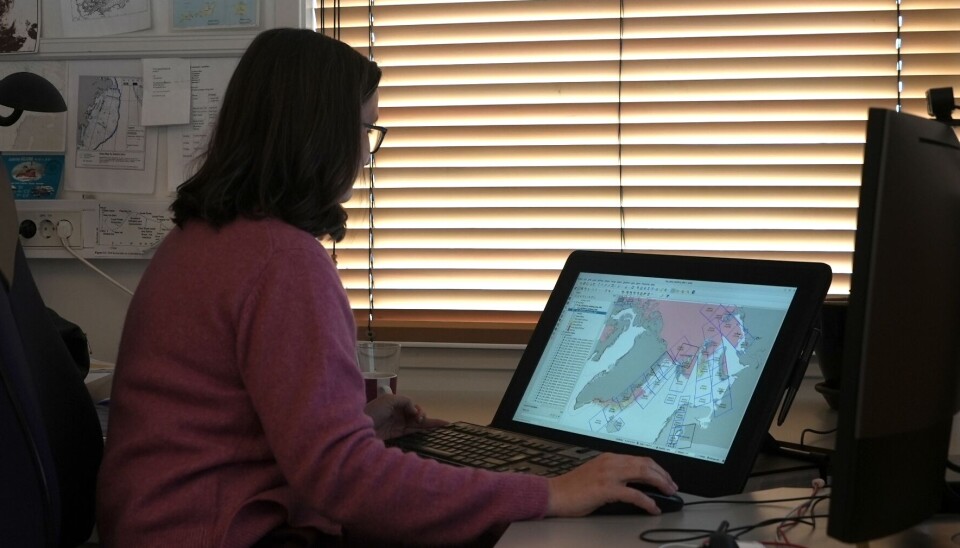

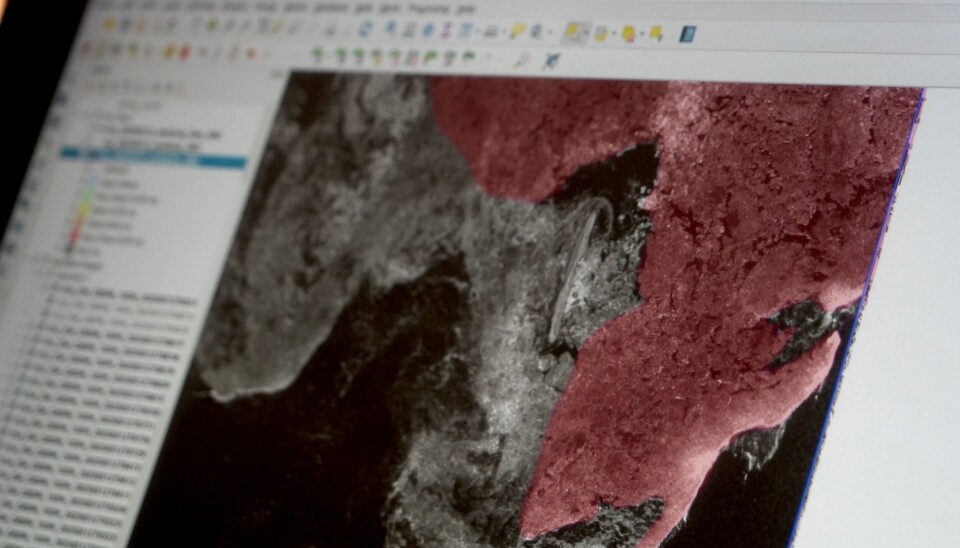

"I look at the satellite images and then I manually draw the ice extent from what I see in the images, - Signe Alvarstein, MET ice analyst, tells the Barents Observer. “For example, today I can see that big changes happened this weekend. Winds from the south have pushed ice northwards around Svalbard”.

Signe carefully distinguishes between the blue water and the greyish colours of the ice on the satellite pictures, and draws a purple line to indicate the extent of sea ice for the day. As the MET researchers point out, AI can't yet replace humans in this task.

Signe has been doing this work for almost 30 years. That is long enough to see the changes that are happening to the Arctic:

"I can see that there is less ice in the Barents Sea than there used to be. But it varies from year to year," she says, looking at Novaya Zemlya on her monitor and continuing to draw a line.

Much of the world would rely on such data, especially at a time of uncertainty for American science as the US government cuts funding for climate research at home and abroad.

With the recent announcement that National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) was downgrading its support for data products that document the extent and thickness of sea ice, the data produced by European and Norwegian institutions, such as the MET, will become even more crucial to understanding the extent and speed of climate change on our planet.

“I dont think it is a question anymore if climate change is real, - Signe Alvarstein says, - “It is real. There are so many signs of it. We see the changes year by year, and we have lots of data going back in time”.

MET researcher Frode Dinessen points out that, according to data produced by the MET, the Arctic winter sea ice extent has decreased yearly by about 38,000 square kilometres each winter since 1980. This is an area roughly equivalent to that of Switzerland.

"When the ice melts, the dark surface of the ocean accelerates its sun warming, and this leads to a further reduction in sea ice", Frode tells the Barents Observer, pointing to one of the maps”.

Outside the institute, there are a couple of devices that measure snow and rainfall.

“Snow is important for Tromsø because we have a lot of it, - Thomas Olsen - Senior Advisor at the Tromsø Meteorological Institute tells the Barents Observer, - "What we are seeing is that the snow season in Tromsø is getting shorter, as it is in the rest of Norway.”

Thomas explains that winter in Tromsø will come a little later and spring a little earlier.

"According to our data, from 1961 to 1990 it was 17 May was the mean date when the snow disappeared in Tromsø, whereas from 1991 to 2020 it was 12 May. The same shift of a few days happens with the arrival of winter".

MET researchers stress that while climate change has happened before on the planet, what we are seeing in modern times is happening much faster:

"One of the main reasons for climate change is the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere. We assume that this rise is man-made," says Frode Dinessen.