“I didn’t hear the usual grinding of ice”

When a Norwegian vessel reached the North Pole this week, the scientific team made an alarming discovery.

“I last reached the North Pole on a research vessel 30 years ago”, the i2B expedition leader Jochen Knies writes in his blog on September 2 after he and the other 47 scientists and crew members on board the research vessel Kronprins Haakon arrived at the world’s northernmost point.

Now, seeing the spot three decades later, Knies realises how much this frozen ocean has changed:

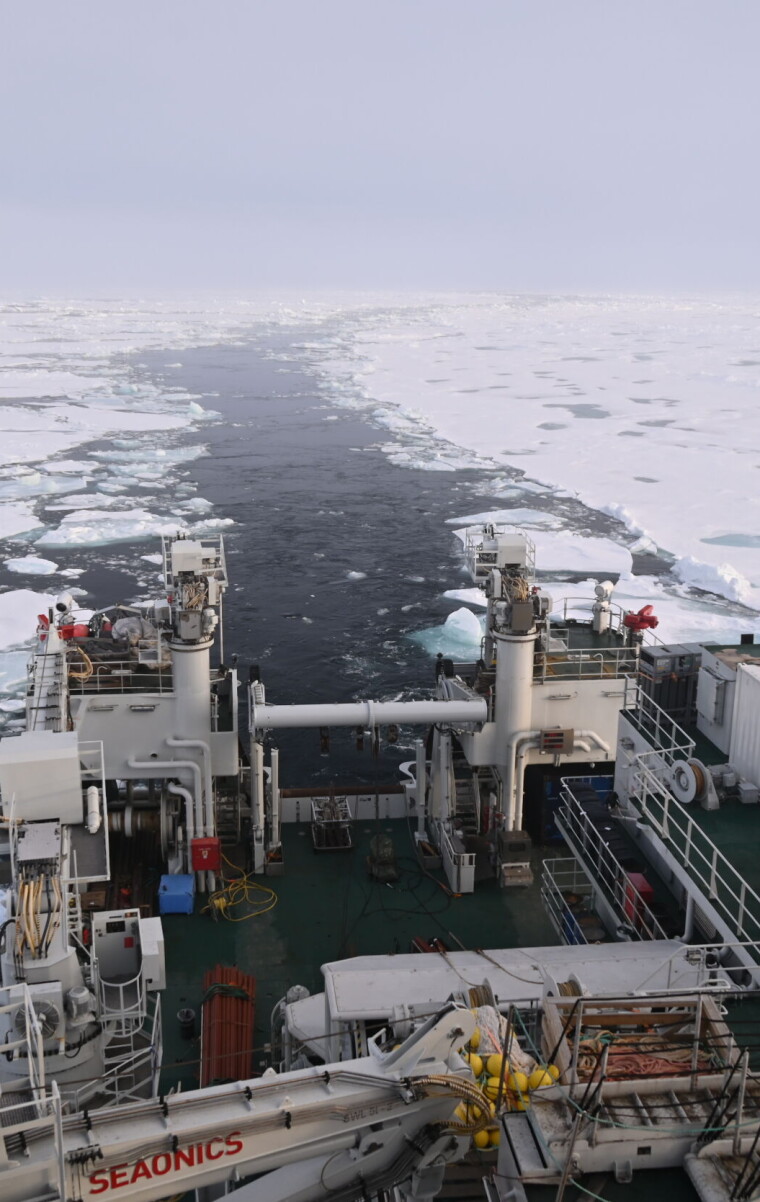

“This time, when I woke at 6 a.m., I didn’t hear the usual grinding of ice. We had been sailing through open water at 6–8 knots, something unthinkable three decades ago”, Knies writes.

Knies and his team of scientists are on a hunt for treasure. But instead of gold, they're looking for clues about the Earth's past climate. They're digging deep into layers of dirt, rocks, and mud that have been piling up on the seafloor of the Arctic Ocean for thousands of years.

Lab analyses of these layers tell us what the Arctic was like when it was last free of ice, about 130,000 and 400,000 years ago. Finding these clues will help Knies’ team to predict the future of the planet once the sea ice has disappeared again.

“When I first sailed to the North Pole in 1996 aboard the research vessel Oden as a young PhD student, I remember one thing above all: ice. Ice of varying types and thickness, stretching as far as the eye could see”, Jochen Knies wrote in an email to the Barents Observer while sailing on board the RV Kronprins Haakon.

“This time, however, the experience was very different. During the first two weeks of our journey—starting from Longyearbyen and reaching the Lomonosov Ridge on August 30th—we encountered large areas of open water."

"There was still sea ice, of course, but our vessel had little trouble navigating through it, thanks to open leads and channels. That’s what struck me most: the ease of access through what used to be a far more ice-covered region,” Knies writes.

According to him, witnessing such a change felt “unsettling”:

“As a scientist, you read and study a great deal about the changes occurring in the Arctic. But reading about it is one thing - witnessing it firsthand is something entirely different", Knies emphasises.

“The transformation is fast. Just as we see glaciers retreat across Svalbard, we see and feel the thinning and retreat of the Arctic sea ice… You don’t need decades of experience to notice it - even the Bachelor students onboard sense that this no longer feels like the Arctic we imagined.”

A German expedition, which travelled to the North Pole earlier this summer on the vessel Polarstern, also highlighted the significant sea-ice changes:

“The sea ice along our route is significantly thinner than expected. We are sailing through open water much of the time, and we are making very fast progress: this is unexpected”, the Polarstern expedition's blog entry on August 10 emphasises.

Meanwhile, the shrinking sea ice is the primary habitat for polar bears.

The reduced ice makes it harder for bears to find prey. Some scientists predict that global warming caused by the emissions of greenhouse gases has already put the polar bear on an irreversible path towards extinction, as the BBC highlights.

BO: But the Earth’s climate has changed many times in the past — even before human civilisation. What makes today’s situation different?

"The pace of change we’re seeing now is unprecedented. Nothing in the geological past compares to the speed at which the climate - and especially the Arctic - is changing today", Jochen Knies replies.

Why is it important for the public to know about these changes?

Knies: The Arctic is the fastest-changing region on the planet - what we call a "climate hotspot”. By making the public aware of these changes, we offer people a chance to understand and reflect.

"They can draw their own conclusions, but sharing firsthand knowledge of what's happening - in real time - can be a powerful way to shift perspectives and drive awareness," Knies emphasises.

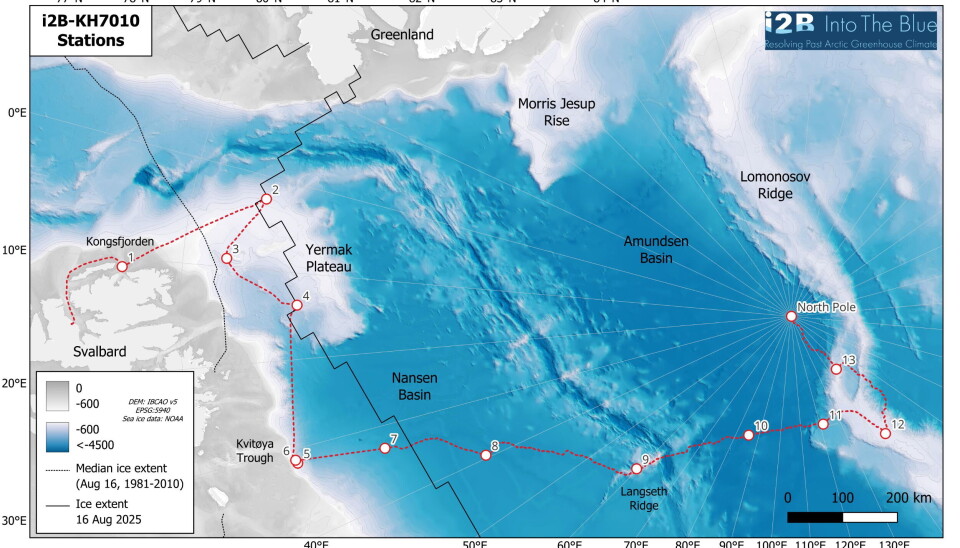

Satellite observations since the 1970s show that the sea ice is melting at a significant rate. The graphic map by Miro Johansson: