“We now risk facing something that many of us might not survive.” Participants of the Pride celebrationbeyond the Arctic Circle — on what it’s like to be a queer person in today’s Russia

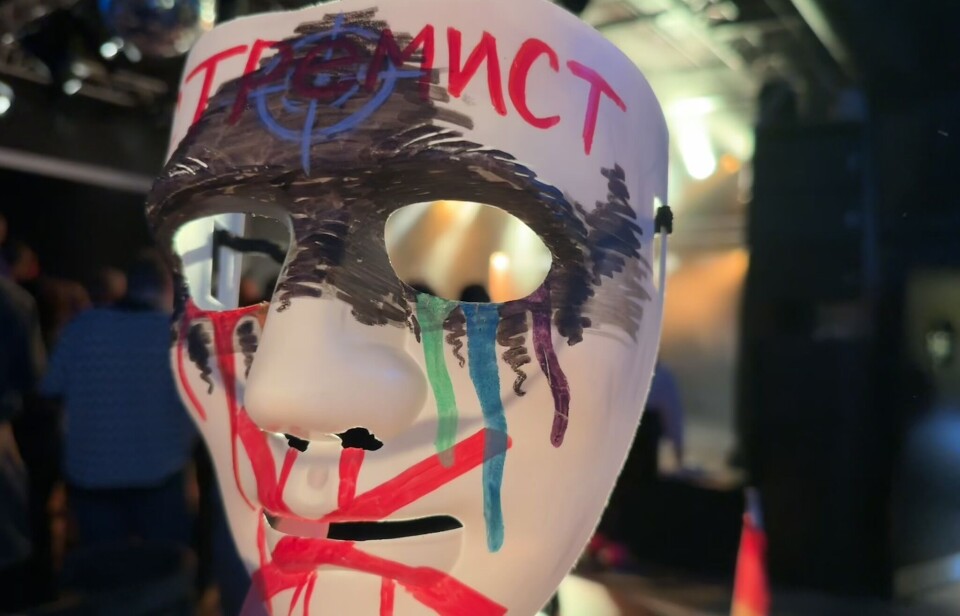

KIRKENES: At the Barents Pride celebration freedom coexists with strict security protocols. Queer people from Russia travel to the event through third countries, cover their faces, and are reluctant to talk to journalists - but they still come, to meet those who accept them as they are. The Barents Observer spoke with Pride participants to understand why they travel to northern Norway and what they feel when they put on a mask.

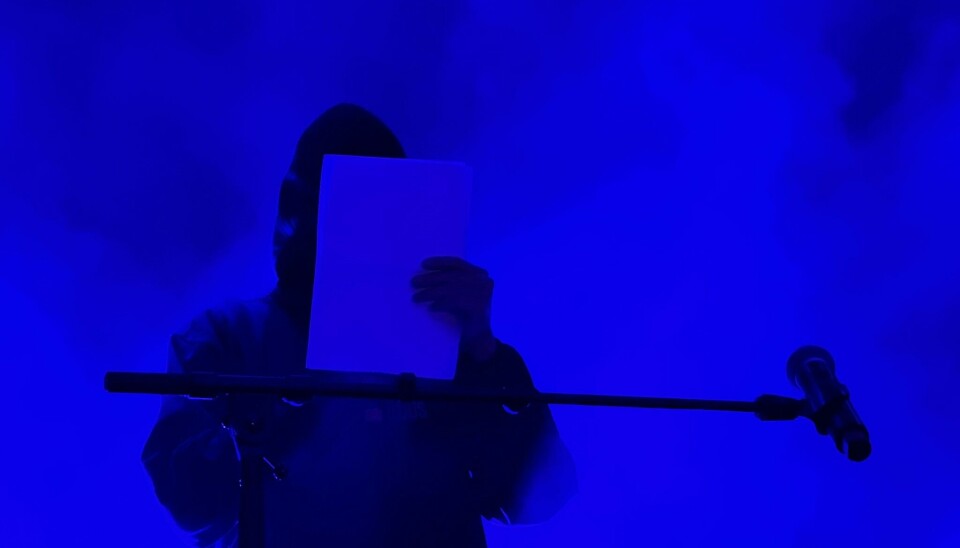

A man in a black hoodie stands on a dark stage. His head is covered with the hood; in front of him, he holds a sheet of paper with text positioned so that his face cannot be seen. We know nothing about the speaker; he isjust an anonymous figure in black, telling the residents of a small town in northern Norway about terrible things.

“We want to tell you about Mark Kislicyn, a young transgender man who was sentenced to 12 years in prison for state treason… We want to tell you about Andrei Kotov, who ran a travel agency for gay men, was detained on extremism charges, and was soon found dead in his cell. We want to tell you about Azat Miftakhov, who has been in prison for seven years; after it became known that he was bisexual, he was harassed by other inmates… We want to tell you about a little boy from the North Caucasus who was tortured, and about homosexual and transgender people from Russia in refugee camps in the Netherlands who took their own lives…”

The appearance on stage was not intended as a performance, says the man in the hoodie, but that’s what it turned out to be. A measure taken under duress to ensure personal safety was transformed into an artistic statement: look at what has become of us, can you feel it?

The man in the hoodie is one of a few dozen Russians who came to Kirkenes in September to take part in Barents Pride. This Pride celebration, located 400 kilometres beyond the Arctic Circle (perhaps the northernmost in the world), has been held since 2017 and was conceived from the start as a cross-border event - the Storskog checkpoint on the Russian–Norwegian border is only 15 kilometres away from Kirkenes.

Today, it is one of the few entry points from Russia into Europe. Yet even residents of northern Russian cities, located practically next door to Kirkenes, travel to Pride through southern countries. The detour of several thousand kilometres costs time and money but helps to avoid encounters with the most inquisitive people in the world - Russian security officers.

All names in this article have been changed for safety reasons.

“Interrogations at the border started in the very first year,” recalls a Pride participant named Artem. “People were detained for questioning, asked to sign blank sheets, told: ‘We’ll find out where you work and we’ll…’ - basically, they were saying they’d out us. They picked out the most vulnerable people - young gay men, young women, people without Russian passports.”

After the Russian Supreme Court declared the non-existent “LGBT movement” an extremist organization, things got even worse.

“ The level of fear and the possible consequences for coming here have changed. Before, they might have wagged a finger at you, but now it’s a criminal matter,” says the man in the black hoodie, laughing nervously.

Before, there was a fear of something unpleasant - but you could get through it. We now risk facing something that many of us might not survive.”

“Just imagine. You live your ordinary life - you stand for love, kindness, and peace. And suddenly you become the greatest threat and the worst criminal for a big powerful country,” explains another participant named Artem. “You’re just a person; you’re not ready for that. And not only that - you’re a person with a lot of vulnerabilities. Because it’s one thing when a murderer goes to prison, and another thing entirely when a gay person does.”

The Pride celebration in the small town of Kirkenes is not the most crowded one, for obvious reasons. But it gives a feeling of intimacy: already the day after the event begins, you see familiar faces on the street. You can ask Grechka, a singer, for a cigarette – this is her first pride celebration and she is happy that she can finally be herself.

“It turned my whole world upside down all at once,” says Kirill, a native of northern Russia, recalling his first trip to Barents Pride. “It turned out that you can live like this, talk about yourself like this, speak freely about your relationships. It made such a huge impression on me that now I come with a very specific purpose - to experience this feeling again and again and to spread it to other people. I take risks for these sensations, for this breath of air, of freedom.”

“You feel like part of a community that is becoming completely invisible in Russia,” says another Pride participant. “Sometimes it happens that even people from the same city, who are fighting for the same thing, don’t know each other. And here there is a small, but real, opportunity to find those with whom you can cooperate. Because there, it’s frightening.”

From Kirkenes to the Russian border it’s a fifteen-minute drive, and during each Pride celebration, solidarity actions are held at the checkpoint. This year, participants shouted “No to war!”, “Russia will be free!”, and - by tradition - did not restrain themselves in the choice of words on their posters.

Complete freedom of self-expression at Barents Pride is closely intertwined with self-censorship. Here, the parade turns around a few metres before reaching the Russian consulate - from the barred windows, someone might take a photo and send it “where necessary.” Here, the Barents Observer tries to talk to one person, then another, then a third - and gets rejected each time. Here, a girl asks us to show the pictures we took a minute ago and deletes the ones where, though barely, her face can be made out.

“To censor yourself at Pride - it’s horrible,” admits a man named Andrei. “ Before, I used to walk in the parade, smiling right and left, talking openly with people, but in recent years - you close yourself off, and not only outwardly, but also inside. Here I am, talking to a journalist now, but I know who you are; otherwise, I probably wouldn’t talk at all.

It hurts terribly, because this is exactly the method the repressive machine uses.”

“It’s really creepy to follow security protocols. You feel like a third-class person. Why should I be hiding?!” says Kirill. “On the other hand, there is some kind of… positivity in this contradiction. A resistance that unites. It gives more value to everything we are doing.”

“It was hard today, during the parade. I look rather noticeable, and at some point the organizers came up to me - ‘Someone is walking around taking pictures, we don’t know who it is...’ And I basically had to just walk nearby. So that, if anything happens, I’d be able to say - ‘I don’t know, I just saw it, just thought it looked cool…’

It hurts quite a lot. I love being in a group, among my people - it’s important to me. Of course, I could put on a hood, wrap myself in something, change into less noticeable clothes, but then that wouldn’t be me anymore. It would be some incomprehensible image for the crowd, for blending into a mass.”

Serafim is a trans man living in one of the northern cities of Russia. He is one of those who managed to transition long before it was banned. In this sense, his life is easier than that of many other trans people in Russia. Well - easier; just not as terrible.

“Here’s an example. I’m a trans man, I have male documents. I need to go to a gynecologist - what should I do? I can’t even make an appointment, it’s impossible. Before, you could come in and say: ‘I’m a trans person, I have this and that.’ Now it’s scary, because I don’t know how doctors will react.

I lived for 15 years with my old documents – I didn’t know what to do or how, there was no information. It was a nightmare, but I had hope that somewhere I would find out something… There was a chance. But now there is no chance, and a person just sits and can’t do a single thing to become themselves. All you can do is suffer, basically, swallow antidepressants by the handful and think about how not to off yourself.”

The motto of Barents Pride in 2025 is “Against all odds” - “In spite of everything.” “It’s a dangerous place for love” - sings a girl from the stage about what it’s like to be a queer person in a repressive state. But an hour earlier, the mayor of Kirkenes, Magnus Maland, reminded the Pride participants that, by his authority, he has the right to officiate marriages. “He can marry us!” - one girl says to another in a piercing whisper; the thought seems incredible to her.

“To be a queer person in Russia means to close off. You go back into your box, collapse, stop trusting the outside world. It’s awful. There are situations when people who were your friends and supported you become influenced by propaganda and start treating you differently. I know more than one such case when even close friends and relatives - although can we even call them close? - say: Maybe you should go somewhere? Maybe you should get treatment? People follow the crowd, follow the state’s narratives. It’s very painful.”

“I can tell you that the state has achieved exactly what it wanted - absolutely, precisely, clearly,” says Artem. “Not only activists are afraid now, but ordinary people as well.

You go to bed - you are afraid; you eat - you are afraid; you go to the store - you are afraid; you go to school, to your child - you are afraid; you meet someone - you are afraid; you talk to your parents - you are afraid…

But the value of Pride has changed. How precious it has become to see each other, to hug each other! To understand that it’s not you who have gone insane - it’s the world that has gone insane.”

“What keeps us afloat: people are still people,” says a Pride participant on the first evening, when everyone is getting acquainted.

Kirill echoes him: propaganda creates a feeling of absolute hatred, but - and in this case without any sarcasm - not everything is so clear-cut.

“I’ve got the impression that young people, especially zoomers, have a much simpler, more reasonable attitude. I think it’s the same as with the war. Even inside Russia there are still a lot of people who perfectly understand that what they’re saying on TV is bullshit.

You know, I really love Pikabu (an informational and entertainment online community - editorial note). And sometimes there are jokes or news related to LGBT topics there. I always look into the comments, and more and more often I see that the top comments are either something positive toward us, or something sort of shitty-neutral - like, ‘let them do what they want.’ So I get the feeling that, for the most part, people at least don’t care.”

To come to Kirkenes, exhale, fill your lungs with oxygen - and go back home. That’s the plan for Serafim, Artem, Kirill, and other Pride participants from Russia. The country that has declared them outlaws still remains their home.

“We keep gathering. We drink tea, play board games, share experiences. We walk the streets more or less freely; nobody grabs anyone from the crowd. We go on social media - we don’t touch political topics, but we talk about how one can live, how one can be friends with oneself, how one can accept oneself,” says Serafim.

“Yes, we have to assimilate a little: not be too obvious here or there… But still there remains a hope that somehow, somewhere, it will get better.

I mean, for me the best I can do now is to go, to see, to hang out, to talk. The people abroad can’t help us in any way. What can they do? They can say [to the Russian authorities]: ‘Guys, have you lost your minds?’ They’ll be answered: ‘Well, yeah, we kind of have. But go to hell.’”