The Arctic at risk from plastic

A new research report shows that the Arctic is under threat and may suffer negative impact if plastic enters the food chain.

Text: Helge M. Markusson, The Fram Centre

Researchers Claudia Halsband from Akvaplan-niva and Dorte Herzke from NILU (Norwegian Institute for Air Research) have reviewed currently available published research material on plastic pollution in the Arctic. The material shows that this new type of pollution is also causing problems in an area at great distance from the densely populated parts of the world.

“Despite the fact that the research covers a vast geographical area and is based on varying methods, it is apparent that plastic is ubiquitous in Arctic environments,” confirm both Claudia Halsband and Dorte Herzke.

Global problem

The increase in the volume of plastic litter is directly related to the increase in plastic production every year. When mass production of plastic started in the 1950s, annual production volumes were less than 2 million tonnes. 335 million tonnes were produced in 2016.

Plastic pollution in general – and in the world’s oceans in particular – has emerged as a major environmental problem worldwide, and is now acknowledged as a threat to all ecosystems. More recent estimates predict that 5-12 million tonnes of plastic end up in the world’s oceans every year.

The data reviewed by the researchers in Tromsø show that the impact of plastic litter pollution is just as severe in the Arctic as in more populated areas farther south. Further studies are required to uncover whether this is particularly the case for the European Arctic area, which has a huge flow of water from the Atlantic Current.

Sources

There are many reasons why plastic ends up in our oceans. Mismanagement of waste from coastal towns and cities situated on large rivers and insufficient wastewater treatment, are the main entry routes for plastic litter in the oceans.

Growing urban populations in the European sector, Canada and Alaska will generate more plastic litter than the depopulating rural areas along the Russian coasts, and will generate accumulations of plastic litter in the Arctic. The flow of plastic into the Arctic environment from land depends on local and regional developments. Moreover, the implementation of appropriate waste facilities and recycling plants – or the lack of such infrastructure – will have a vital impact. Purification plants for wastewater, for example, are not common in thinly populated Arctic regions.

Plastic litter is directly proportionate to plastic consumption. Plastic litter from industrialised and densely populated areas is dispersed into the environment on a global scale. It also reaches the remote and seemingly untouched Arctic Ocean.

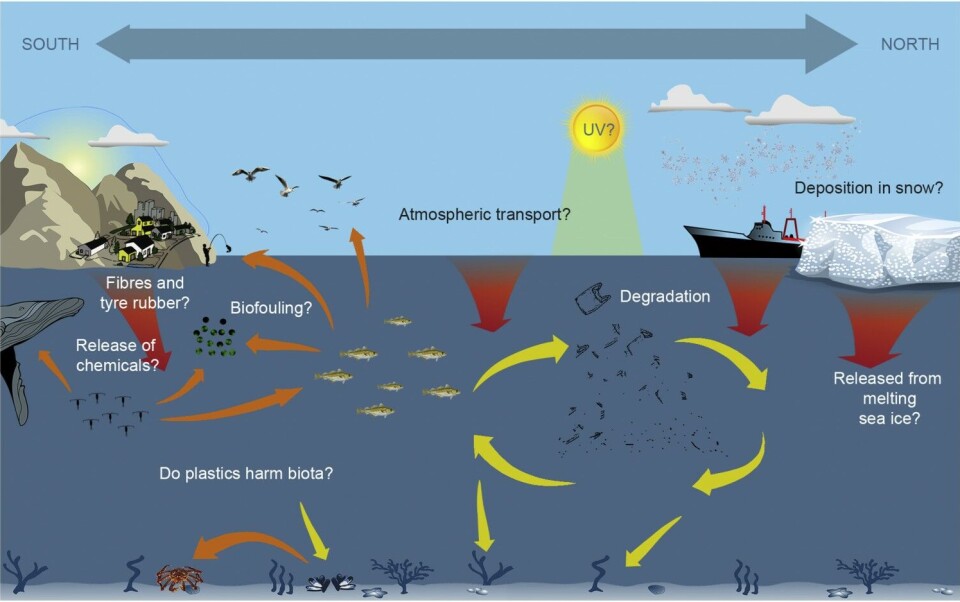

The ocean currents carry the plastic with them. Several large ocean areas, such as the Fram Strait, the Bering Strait and the Alaskan Archipelago, provide direct access to the Arctic. However, atmospheric distribution with winds also plays a role in long-range transport of plastic, particularly the smallest particles of plastic.

Important to understand distribution patterns

The very first reports of plastic pollution in the Arctic date back to the 1970s. Research published in 1980 describes observations of marine plastic on beaches on Amchitka, one of the Aleutian Islands in the Bering Sea. The intertidal zones on the beaches were surveyed once a year for a period of three years, showing that the total number of plastic pieces increased from more than 2,200 to more than 5,300 in a two-year period. The accumulation rate by weight was almost 60% per year. Most of the plastic litter came from fishing vessels, but some objects had travelled more than 1,000 km from the Asian coast. This was the very first demonstration of long-range transport of plastic.

“If we are to understand the transport of plastic litter into the Arctic, we first have to understand the regional distribution patterns within the Arctic, and temporal trends. We need knowledge of local sources, as well as understanding that their contributions to plastic pollution in the Arctic are of importance. But we also need knowledge of the sources and transport pathways from more densely populated areas farther south,” says Claudia Halsband.

Insufficient knowledge

In their published article, the two researchers conclude that we currently lack sufficient knowledge of the dispersal and effect of plastic litter in the Arctic.

“The Arctic is under threat and may suffer a negative impact if plastic enters the food chain. Taking into account the fact that macroplastics and, in particular, microplastics cannot be efficiently removed from the Arctic, we need to obtain a deeper understanding of the situation. Even more importantly, we need to understand what will happen when this interacts with climate change, pollution by other environmental toxins and ocean acidification. Future studies should focus on filling the current knowledge and data gaps, as well as their relevance for risk and impact assessments,” say both researchers.

This story is originally published by the Fram Forum