“There’s no way back”

The story of the Russian soldier who deserted from the war in Ukraine and ran across the border to Norway after nearly two weeks in the wilderness.

After coming out of the water, exhausted and drained, "Sergei" began waving his arms toward the surveillance cameras installed along the border, hoping to be detained. He had just waded across Grense Jakobselv, the shallow creek forming the borderline between Russia and Norway. Reaching the nearby narrow road, he noticed a military vehicle approaching. Inside sat two young men in uniform. Sergei waved again - essentially trying to surrender. But instead of arresting him for illegally crossing the border, the soldiers only smiled and waved back. Sergei recalls this moment with laughter: he expected to be detained, but instead saw nothing more than an ordinary Norwegian greeting.

"Three or four drones with grenades flew over us. They started dropping them. I ran in zigzag between the trees. I saw a shelter. There was a corpse at the entrance. I went right over it, over that dead, rotting body, and climbed inside."

Then came the blast. Sergei’s leg was fractured, the other wounded. “I took out a cigarette and thought: the last one before death. And you know how bitter it was when I couldn’t find my lighter? I was really upset.”

It was at the military hospital in Moscow that Sergei decided to never return to Ukraine. A few weeks later, after a strenuous walk across the wilderness of the Kola Peninsula, he waded the creek at Grense Jakobselv and was in Norway.

"Sergei" is not his real name. He is speaking on condition of anonymity. Our interview takes place next to the refugee camp, about an hour’s drive from Oslo.

He was born in Yakutsk — the capital of the Sakha Republic, where winters are harsh and temperatures often drop to minus fifty. Later, together with his wife and two children, he moved to the Moscow region. There he worked at a law firm, while also taking side jobs as a taxi driver and a security guard.

An ordinary family life, just like everyone else, he says.

Sergei never imagined he would end up at war. At eighteen, he wasn’t even drafted into the army - he was classified as “fit with limitations.” But in April 2024, everything changed: at the military enlistment office, he was declared healthy and had to sign papers without any explanation of what they meant. Just a few days later, he found himself at the border with Ukraine.

Looking for a way out

“In general, I started thinking about escaping when I ended up there — in Ukraine. I even had thoughts of self-harm. I met guys who were asking others to wound them, just to get taken out of Ukraine. Do you understand how bad it was there?” says the former soldier.

“I didn’t know how to get out of the war,” Sergei continues. “There are so many people who hurt themselves. They put on two or three bulletproof vests and throw a grenade at themselves. That way they get injured. But still - everyone gets back. Even those who were taken prisoner. Anyone who still has limbs is sent back to the front. It doesn’t matter what condition they’re in.

I even met people with cancer who were sent there.

While in the hospital after being wounded, he studied escape routes: Kazakhstan, Georgia, Armenia, Belarus - one option after another crossed his mind, but there was a practical barrier: he didn’t have a foreign passport, and his internal one was badly damaged. Sergei searched for a solution by looking at the map.

That’s when he came across an article about a Chinese citizen who had crossed the Russian-Norwegian border back in 2015. “I looked at that map through the eyes of a Chinese man and saw a possible way out. He had made it across 10 years earlier; I read about it in the Norwegian press,” Sergei recalls. This knowledge became a point of support. He made his decision.

To prepare for the escape to Norway, the former soldier turned to YouTube channels. There, he studied the experiences of Ukrainian soldiers who had illegally crossed into other countries: “Those guys share their stories, how they got out of Ukraine. Through Romania, Moldova. So there’s information: what they used, what obstacles they faced on the way, what troubles they ran into. You see, I never had any experience with hiking, tourism, mountaineering, anything like that.”

The man also did physical training. He knew he would have to walk most of the time: “Before leaving Russia, I trained - I put bottles of water in my backpack and walked. I was preparing my body so there wouldn’t be muscle soreness.”

From Moscow to Murmansk, Sergei travelled by taxi. He knew he couldn’t use public transport. The details of all tickets that are purchased go straight to the FSB; they have a special database for this called “Rozysk-Magistral.”

From outside Murmansk, he continued on foot - all the way to Norway. He had two phones with burner SIM cards, as well as a smartwatch for navigation. He had used them during the war.

Sergei spent 15 days on the road. He says the journey took longer because of the wound he’d received and problems with his legs. He wore a camouflage outfit “but not like the military - more like hunters,” he notes.

During our interview, the ex-soldier unexpectedly asks me to take my phone off the table. “Water might get on it,” he explains as the rain gets more intense. I told him that the iPhone, from which our interview is recorded, is waterproof. Sergei smirks and talks about his own phone which was damaged along the walk in the wilderness: water got into the camera when he swam across one of the rivers.

I went through rivers and through lakes. There was more than one river on my way.

Sergei recalls one moment when everything could have fallen apart. “In Pechenga, I was walking across a bridge at night and almost ran into a road worker. He could have reported me,” he says. Otherwise, Sergei hardly saw any people along the route: only distant conversations and shouts carried from afar. In his words, it’s easy to tell where people move through the forest by its condition - there you find glass bottles, tin cans, and food wrappers.

Sergei is wearing the cap and boots he used during the escape. “German! Original!” he notes.

At some point the food began to run out. Sergei ate berries: blueberries and lingonberries. Around him, as he recalls, there was incredible beauty - the northern landscapes stayed with him in vivid detail:

“I saw such beautiful views. There isn’t a single postcard with those kinds of northern vistas. It’s so beautiful. Imagine, I saw a lake about ten kilometres long. A rift in the mountains, and in the distance you could see the ocean. The actual waves of the ocean. Very beautiful,” he recalls.

The white nights in mid-August made the space feel even more unreal: shadows didn’t fall, and even the time of day lost its meaning. At such hours he pitched his tent, but sleep wouldn’t come - it was too bright and unfamiliar.

His first target was the border fence - the one built on the Russian side that doesn’t mark the border itself. Usually there are several kilometres of empty land between the barrier and the border line. But he knew of a place where that distance narrowed to just a few dozen meters.

Crossing the barrier was nearly impossible: in front of it there is always a sand tracking strip, and touching the metal instantly sends a signal to the border guards. But then - he got lucky. There was a hole in the fence. “I didn’t know about it,” he recalls. “I just happened to come out right there by chance.”

The Barents Observer has not been able to independently verify this information.

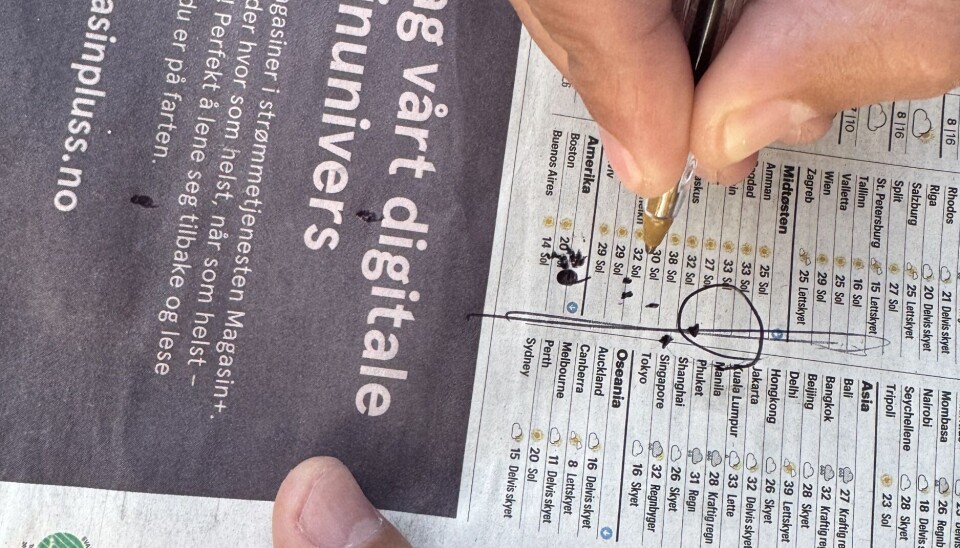

On a newspaper he sketches a diagram. Sergei explains that such fences are installed around the entire perimeter of Russia: “Since Soviet times,” he emphasises.

Sergei spent one of the nights among military fortifications from World War II. He says he also found a wartime helmet there: “If you did excavations there, I think you could find a lot.”

When only a few meters on the way to freedom remained, Sergei stepped into the water of the Grense Jakobselv creek, which separates the two countries. At the very edge he noticed a fish sliding right by his feet. It was early morning with sunrise over the river.

Clambering onto the other bank, wet and exhausted, he began to seek help. The attempt to stop a military vehicle ended only with a smile and a friendly gesture from the Norwegians. But soon he met a man whose house stood right on the border. The man called the police. From that moment, a new path began for Sergei - the path of a refugee.

Miraculously deemed fit and healthy

Sergei is just over 40. He was born in the city of Yakutsk - the capital of the Sakha Republic in Siberia. Later, together with his wife and two children, the family moved to the Moscow region. There Sergei worked at a law firm and for a time took side jobs as a security guard and a taxi driver. “It was an ordinary family life, like everyone else’s,” the man recalls.

In April 2024, employees of the local draft office in the Moscow region called Sergei. “They said I needed to come in to update my information. I came and immediately heard that the next day I had to show up at the assembly point with my things,” he says.

The next day came the medical exam. At eighteen, Sergei had been assigned health category B4: “fit with limitations,” and wasn’t drafted then. But now the doctors suddenly decided he had recovered. “They assigned me category A2. So apparently I recovered over all these years. Miraculously I became fit and healthy,” the former soldier laughs.

Sergei says he had no idea what exactly he was signing. According to him, the staff misled him and essentially tricked him into signing a contract with the Ministry of Defence to take part in combat: “You understand, I was in such a state that I didn’t even look at the papers I was signing. It felt like a routine thing - sign and that’s it,” he says. Just a day after the phone call, they were taking him toward the border with Ukraine.

“I understood only one thing: that’s it, they’re taking me - there’s no way back,” he continues. In his words, at that moment it looked as if he had voluntarily agreed to go to war.

At the draft office no one explained what awaited him. “Before the medical exam I didn’t even realize it was war. And when they assigned category A2, everything became clear.”

After the formalities, Sergei and others were sent to Kursk Oblast, to a training ground. There was no training at all: the man didn’t even have shooting experience. “They issued a uniform, an assault rifle, and a bank card. In the military ID they entered my position - reconnaissance scout. They said, ‘Don’t pay worry about it.’ In the end, half our people were listed as cooks and half as scouts.”

As the ex-soldier notes, positions in wartime are often assigned almost randomly: “As long as there’s a person, a position will be found.” At the post where Sergei served, the role of doctor was performed by a veterinarian.

I had never even fired a shot, but they issued me a weapon.

Sergei and other servicemen were transported by military trucks to Kharkiv Oblast. He spent half a year there until he decided to escape.

“Do you know how much time passed from when I got to Kursk to when I ended up in Ukraine? Five days. So there was no training at all, nothing. I had never even fired a shot, but they issued me a weapon.”

At first, Sergei cleared trenches. “They had already been dug but were clogged with branches and trash. You could say I was tidying up,” he recalls. A week later, the platoon commander told him to go on duty - to relieve someone. They hauled a generator and food and reached the shelter.

“The dugout was a two-by-two-meter space. Basically a burrow. Logs, little branches, plastic sheeting on top. About twenty centimetres of earth piled over it,” Sergei explains.

And it’s precisely such shelters, he says, that can’t withstand a strike by “Baba Yaga” - the Ukrainian drone soldiers nicknamed after a fairy-tale character. “It’s an agricultural drone. Big, one and a half to two meters, with eight rotors. It can lift four anti-tank mines or four rounds from an anti-tank grenades,” Sergei says.

For a dugout to withstand a “Baba Yaga” attack, you need eight “courses” — eight layers of thick logs. Sergei’s dugout had two layers with branches on top. “Imagine if a drone with mines hits that.”

Sergei worked in electronic warfare. They had various EW systems - “some like guns” - and he had a compact suitcase: “You open the lid and a stream of radiation comes out that hits the enemy’s radio communications.

“The controls are simple: the panel has a dial with a pointer - set it to ‘11 o’clock’ and the case jams everything in the sector corresponding to 11 o’clock.”

“So this device would bring down drones?”

“Well, I wouldn’t put it that way,” Sergei laughs. “It creates some interference for whoever is controlling it - a drone, for example.”

During the conversation next to the refugee centre in southern Norway, two young Russian speakers walked by, and Sergei abruptly fell silent. They turned out to be guys from Ukraine.

Sergei almost in a whisper: "They’re my neighbours from the camp (for refugees). I haven’t told anyone here that I’m from Russia and that I fought.”

“Why?”

“Can you imagine,” he said, looking toward the passersby, “that some of them have relatives who suffered? Some might even have lost loved ones because of Russia’s actions.”

Speaking about his daily life, Sergei repeatedly returns to front-line losses: “You know, most soldiers - maybe they’ll last a day, maybe five days, and that’s it… Either wounded or killed. They carried us there in trucks, there were about a hundred of us. And when they took me away after I was wounded, I knew of only five who were still unhurt. That includes me. But even I was wounded. The losses are enormous.”

When the journalist remarks on the number of identified dead, Sergei replies: “Do you know how many guys are lying there? Unidentified.” At that moment he fixed his gaze on a single point; the horror stirred by his memories was visible on his face.

“Sorry,” he said, and continued: “There’s just a body lying there; to retrieve it, you need at least two people - they’ll lie down next to it and end up there too. It’s unsafe to recover them. They’ll die there. I’ve heard about special evacuation teams: they only take parts - they cut off a hand, a leg, a head, and send them for DNA testing. Personally, they never took my DNA - I’m not in any databases.”

The last cigarette before death

Sergei had faced the deaths of comrades more than once, and one day he himself was on the brink.

One evening a brief order came over the radio: “Prepare your things,” with no explanation. In the morning a guide came to them and led three people, him and two other soldiers from the posts, through a patch of scrub, along a path whose very edge was lined with mines. “I didn’t know whose they were - Russian or Ukrainian,” Sergei recalls.

“And then I heard an explosion. The guy who was coming from the other post stepped on a mine dropped by a drone. The drone flies up, drops it - the mine falls and extends little wire whiskers. And that guy set it off.”

According to Sergei, this is what modern positional warfare looks like: any movement here is almost a death sentence. People still imagine battles as in World War II - crowds charging, tanks rolling, cries of ‘hooray’ gunfire. Today it’s different: mortars, drones, machine guns, and tanks blanket any activity. “All those people who run out… they won’t make it even a hundred meters - everyone will die.”

“I hoisted that guy onto my shoulders and dragged him,” Sergei continues. “We dug a shelter where we could hide. We laid the wounded man down. And there I saw a huge number of dead.”

One of his comrades told him: “Look, two of our brothers are lying here. Dig in somewhere nearby.”

From memory, Sergei began sketching on a newspaper the placement of the bodies he remembered. At that moment during the interview the weather suddenly changed: the sun gave way to a thunderstorm and a downpour. Sergei quietly said, “Rain is good. It’s always salvation. And strong wind is good. Nothing flies.”

Then he heard the hum of a reconnaissance drone. Almost immediately three or four drones with grenades appeared after it. “They started dropping them. I ran in a zigzag between the trees. I saw a shelter - an old dugout. There was a corpse at the entrance. I went right over it, over that dead, rotting body, and climbed inside.”

His ears rang from the explosions. One leg had a fracture, the other a shrapnel wound.

“I took out a cigarette and thought: the last one before death. And you know how bitter it was when I couldn’t find my lighter? I was really upset.”

After this wound, Sergei was taken to a military hospital in Moscow. The command gave him 60 days for rehabilitation. But it was there that he made his final decision: never to return to Ukraine again.

Ukrainians are defending their home

Sergei is now in a refugee camp about an hour’s drive from Oslo. He was sent there after he requested political asylum during a police interrogation. At first, a case was opened against him for illegally crossing the border, but when he explained his motives, the investigation, it seems, was closed.

According to him, before fleeing Russia, he had prepared himself for torture and humiliation from both sides. But on the Norwegian side, the police received him peacefully: for a short time, he was handcuffed. As Sergei himself jokes, he even had to help the officer fasten the cuffs properly, otherwise “I might have run away.” The former soldier spent a couple of hours in a cell at the police station in Kirkenes. There he was given food and a radio. Sergei turned on the music and fell asleep. It was the most peaceful sleep he had had in weeks.

At the refugee camp in southern Norway, life drags on monotonously. However, soon he is to be relocated to his own housing. Sergei admits that out of boredom he spends entire days walking around the area and looking at cars - he has always been passionate about vehicles. Now, he says, he dreams of saving up for an electric bicycle to go on rides.

In Norway, Sergei feels safe. But sometimes anxiety still creeps in: “Sometimes I look at the neighbours and think: maybe one of them is a major from the security services. And then I catch myself thinking: So what? What could he do to me?”

He doesn’t know if Russian security forces are looking for him, but he calculates the possible charges himself: desertion, illegal border crossing, and probably treason. There is no way back for him. “Do you know who Boris Nemtsov, Alexei Navalny, Yevgeny Prigozhin are?” he lists. “They are completely different, but all were killed on Russian territory. And everyone understands by whom. But no one will ever be able to prove it officially.”

Sergei speaks of the war cautiously but firmly: it was there that he first realised a human life can be worth nothing. “It’s not that it’s priceless, as in valuable,” he explains. “On the contrary: its value there is zero.”

He gives an example. In a village not far from their position, the forest gave way to a field, and beyond it stood residential houses. “If we were sitting in the open like this,” he says, gesturing, “in war it would be fatal.”

Once, a sniper observing nearby reported over the radio: he could see a soldier being led across the field. The soldier had been punished for some offense and was sent to collect fallen drones. “Well, you understand… What happened to him? Of course, he died,” Sergei says. The sniper later helped retrieve the body back into the forest. “And what did he die for? No one knows. Maybe he drank. Maybe something else. But certainly not for truth or for victory.”

How this war will end, Sergei does not know. But he is sure that Putin’s regime benefits from it: “Thanks to this war, Putin remains in power.”

Sergei admits that at the front he rarely met people motivated by ideology. “It’s different here. Most go for the money. And most understand: we are on foreign land, on the territory of another state. Many understand that Ukrainians are defending their home. They just don’t have a way out. I found a way out for myself, but many stay. Maybe they don’t even think that there could be another choice.”

Sergei’s story is not an exception but part of a broader picture. Court records from Russia’s northern regions show more than 800 convictions for unauthorized absence, desertion, and feigned illness since the spring of 2022, with a sharp increase in Murmansk and Arkhangelsk regions, as well as in Karelia and Komi.

Nationwide, according to an internal briefing analyzed by Frontelligence Insight and InformNapalm, 50,554 cases of refusal to serve were documented in 2024, while the human rights initiative Idite Lesom (“Get Lost”) reports that it assisted 46,323 Russians seeking to avoid mobilization.