What can 40 years of reindeer monitoring data tell us?

Svalbard reindeer live in the most rapidly changing Arctic environment. The 40-year monitoring shows population growth and increased carrying capacity of the tundra, but also harsher winters, greater isolation, and population reductions. Population developments thus diverge in the two core monitoring regions.

By: Åshild Ønvik Pedersen and Virve Ravolainen // Norwegian Polar Institute

1.

Svalbard reindeer have attracted research interest for decades. Occasional counts and “guesstimates” of the population have been made since the early twentieth century, but systematic population abundance censuses did not start until the late 1970s. These annual counts have given new insight into many aspects of the ecology of the northernmost wild reindeer, which inhabits a simple trophic food web, where insects and predators have less importance than further south.

These reindeer time series form a core of the reindeer monitoring module of the Climate-Ecological Observatory for Arctic Tundra (COAT). The data have demonstrated that mainly density-dependent processes and weather variability determine the number of animals. Currently, the monitoring is being supplemented with data on individual animals obtained from capture– mark–recapture programmes in the coastal and inland monitoring regions. Combined, this information has made the Svalbard reindeer a model species to understand climate influences on Arctic herbivores.

Reindeer growth rates and climate

Rapid, dramatic climate changes have taken place since the monitoring started four decades ago. The reindeer have lived through both cold, stable winters in the 1980s, and milder, rainier winters that started to become more frequent in the 1990s, a trend that has accelerated rapidly into the new century.

The increased occurrence of mild, rainy winters has led to negative growth rates through increased mortality and reduced reproduction. This is because the plants the reindeer eat become inaccessible – encased in solid ice for some or all of the winter season.

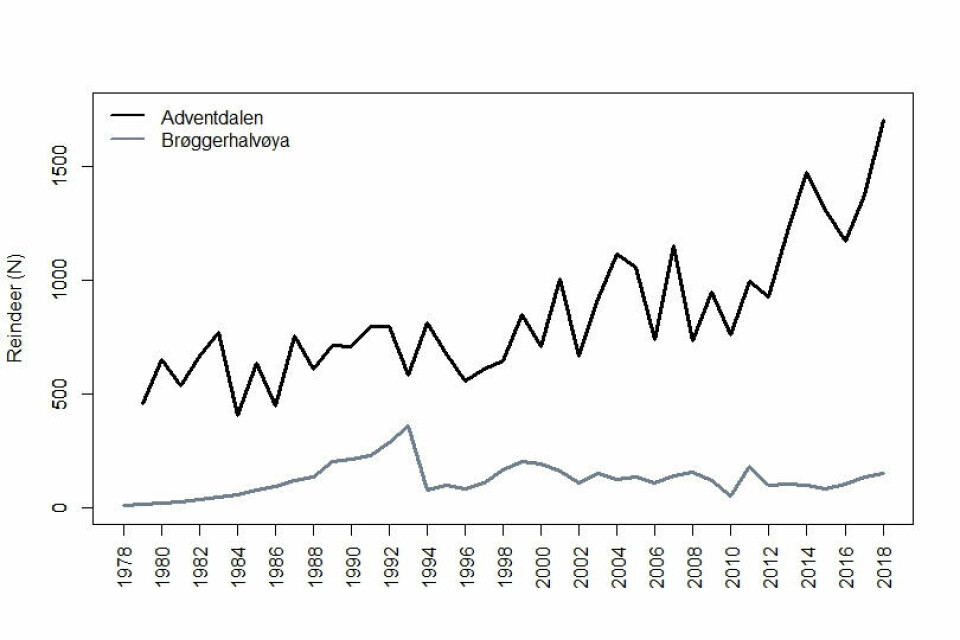

The reindeer population crash in Brøggerhalvøya in 1993/94, for example, followed from a combination of heavy rain in early winter and overgrazed pastures. The population declined sharply to a lower level, where it has since stabilised due to an overall long-term reduction of the carrying capacity of the tundra in this High Arctic coastal region.

2.

In contrast to Brøggerhalvøya, the monitoring areas in Adventdalen show positive reindeer population trends over the monitoring period, despite population declines during winters with “rain-on-snow” events. In Adventdalen, the population has nearly quadrupled, with a record high number in 2018. Here, the higher summer temperatures likely play an important role in increasing the overall carrying capacity of the Arctic tundra for grazing reindeer. Plant biomass production is highly correlated with summer temperatures. Given that the summers continue to be warm and there is enough rain, we can expect food resources to remain more abundant. If autumns continue to have less snow, the food will be available longer during the autumn and into the winter.

The climatic drivers – warmer summers and milder winters – will likely affect the monitored populations in different ways and cause the contrasting population developments in the monitoring areas. Currently, the time series are helping us understand how climatic drivers result in the disparate population trends seen over the last four decades.

Shifts in seasonality and reindeer body mass

The shifts in seasonality affect the reindeer in various ways – and it all comes down to how weather variability and climate affect the food supply. Herbivores owe their survival to plants – mosses, grasses and herbs that are cornerstones of the tundra vegetation communities. Warmer autumns give the animals longer snow-free seasons and better possibilities to accumulate body reserves before entering the winter, when snow makes grazing more energy-demanding.

The capture–mark–recapture studies of female reindeer from the most productive areas in Svalbard, the large inland valleys of Nordenskiöld Land, provide novel knowledge on the contrasting effects of summer and winter warming on individuals and population dynamics. The winter body mass of the females explained almost all variation in the between-year fluctuations of the population growth rate because it strongly affected reproduction, which in turn affected subsequent survival and recruitment. A warm October positively influenced ovulation rates and a warm autumn was associated with higher body mass in April, reflecting the delay in onset of winter with the extended season for grazing without snow.

In contrast, body mass in spring was negatively related to “rain-on-snow” events. The increased reindeer mortality in such years provides crucial food resources for the arctic fox, which may bring about cascading impacts on other herbivores (geese and ptarmigan) in the food web. The net outcome on individuals and their population dynamics will depend on the relative role of winter versus summer change.

While continued climate warming can increase the carrying capacity of the Arctic tundra, winter processes can change the net effect of climate on reindeer population dynamics. The more frequent ground ice in winter, and winter warm spells that can melt away snow and make forage more accessible can have differing effects depending on how much the changed winter conditions damage the forage plants. Ultimately, the outcome for individuals and populations is determined by the cumulative effects. To disentangle and separate the individual effects and the net outcome on reindeer populations, both long-term sex- and age-structured monitoring data and capture– mark–recapture data are essential.

3.

COAT reindeer and vegetation monitoring

The Svalbard reindeer population was severely depleted by hunting in the early twentieth century. Although it recovered after becoming a protected species in 1925, questions remain regarding the population’s robustness and ability to adapt to a completely new climate regime and an altered Arctic tundra landscape. Since this endemic species is a key herbivore on the Svalbard tundra, the COAT programme has focused on monitoring the reindeer, its grazing resources and interactions within the food web.

The reindeer monitoring addresses direct impact pathways on reindeer survival, for example, the effects of climate (winter versus summer warming) and management (hunting quotas). Indirect impacts are also studied. Changed abundance of reindeer can affect plant communities through changed grazing pressure (e.g., drive the vegetation from moss- to grass-dominated); trampling and fertilisation of the tundra may also contribute to vegetation state changes. The module also addresses how the goose populations – which have grown substantially during the four decades of reindeer monitoring – might compete for vegetation resources. The vegetation monitoring links climate-related data (e.g. temperature, snow, basal ground ice, etc.) and time series of grazing animals, both reindeer and geese, to the abundance of functional plant communities and key plant species.

These are examples of how the COAT programme focuses on monitoring the herbivores, the vegetation and the climate in an integrated manner. This broad, integrated approach provides knowledge about the tundra that will be crucial to management efforts.

The time series of the Svalbard reindeer is an important part of this monitoring, and demonstrate how maintaining ecological data collection over time is important to many aspects of our understanding of Arctic terrestrial ecosystems.

This story is originally published by the Fram Forum