OPINION

Herzen: Now and Forever, a “Foreign Agent”

To further discourage its citizens from freely seeking or expressing the truth, officials in Russia are applying the label “foreign agent” to inspirational figures from the past. Recent examples include Alexander Herzen and his lifelong heroes, the Decembrist rebels. Investigating, defaming, and punishing the dead are just the latest attempts to tarnish the tradition of principled dissent in Russia.

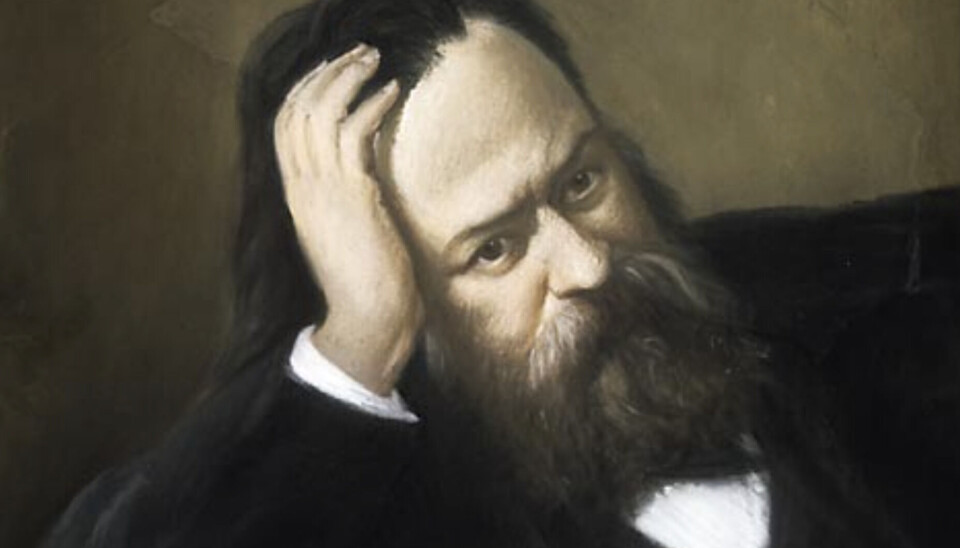

Alexander Herzen (1812-1870), known for an incomparable memoir and bold investigative journalism, can now add “foreign agent” to his posthumous resumé. It wasn’t as if he had a clean record: seven of his 35 years in Russia involved jail, a pro forma death sentence converted into compulsory government service in Perm, Vyatka, Vladimir, Novgorod, and Petersburg – all stemming from a party he did not attend, and a few indiscreet letters to a friend. During Herzen’s 23 years abroad, imperial authorities stripped him of his gentry status and seized part of his inheritance, asked European governments to ban his publications, spied on him, spread disinformation, and threatened bodily harm. There was talk of buying his cooperation, but that was deemed impossible – such was the principled man they wished to silence. Visitors to Herzen in England supplied fresh information for his publications, and some were subject to search and arrest on their return. Even after his death, Russians who purchased and read Herzen’s works abroad often tossed their copies out of train windows before reaching the borders of their homeland to avoid being associated with his ideas.

The twentieth century was much kinder to Herzen, with Lenin’s accolades guaranteeing a steady stream of well-researched volumes, even though some of their Old Bolshevik editors ran afoul of Stalin. Herzen’s stands on freedom of expression and the rights of captive nations appealed to independent spirits like Anna Akhmatova and Natan Eidelman as well as dissidents like Solzhenitsyn who opposed the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia with the same slogan Herzen used to defend Poland, that this was a fight for “their freedom and ours.” In that sense, Herzen became “a man for all seasons.”

Between the glasnost era and Putin’s ascendancy (1985-2000), a number of Herzen’s goals for Russia seemed to have been realized, but as the 21st century progresses, his thoughts about a state whose only goal is power itself, about the premature deaths of young men in Russian prisons, and about how advanced technology can obscure an absence of political freedom, have remained all too relevant. Herzen has recently regained his place as an opposition figure, a publicly named and shamed inoagent. As supporters of the lawyer Sergei Magnitsky learned after his death in 2009, there is no impediment to posthumously convicting people, particularly if they are innocent. Investigating, defaming, and punishing the dead are perfectly logical ways to discourage the living from following their example.

A “Foreign Agent Law” was enacted in 2012 after post-election protests, initially targeting foreign-funded NGOs and their Russian associates. Now such accusations clearly reach into the past. Accused during his lifetime of working against his country’s national interests, Herzen had, since his death in 1870, rested peacefully in his grave on a French hillside until 2022, when, along with the “special operation” in Ukraine, the specter was raised of the foreign operative Herzen, who abandoned his country and supported Russia’s enemies at home and abroad, an example too many young Russians appeared to be following.

One of Herzen’s goals in establishing the Free Russian Press abroad in 1853 was to bring freedom of expression to Russia, and his signature publication The Bell exposed government secrets and widespread corruption, as he sought to undermine the system of censorship that kept the truth from the Russian people. Recently, Putin’s cultural envoy Mikhail Shvydkoy floated the idea of a return to a centrally organized oversight authority for printed sources, just in time for the 200th anniversary of Russia’s first formal system of censorship, established by Nicholas I.

The end of this year also marks the bicentennial of the failed Decembrist uprising on Senate Square in St. Petersburg. As the anniversary approaches, Moscow has preemptively deemed these aristocratic rebels – whom Herzen revered – to be subjects of undue foreign influence. In an open letter from 1857 to Alexander II, Herzen had asked why the government needed to continue insulting the movement’s martyrs, who acted out of love of the country and its people, sacrificing their own lives of privilege. Couldn’t the authorities finally stop lying about the dead and leave them in peace? Was progress in Russia only to be in the realm of strengthening autocracy? Herzen’s questions are as pertinent now as they were then. The government’s answers, unfortunately, have not changed. In Russia, one is never sufficiently dead to escape new charges of disloyalty.

--------------------------------

Kathleen Parthé is author of Russia’s Dangerous Texts. Politics Between the Lines, A Herzen Reader, and the forthcoming biography Alexander Herzen. A Life in Opposition.